The July, 1966 issue (no. 7) of the esteemed Camera Magazine featured a portfolio of images from the Kamoinge Workshop entitled, “Harlem.” This was a meaningful opportunity for Kamoinge, which is said to have been initiated by then-editor R.E. Martinez, presumably after coming through the brownstone gallery space in Harlem, which he is documented as having done.

Camera Magazine was an admired and acclaimed “international magazine for photography and cinematography” based in Switzerland that commenced in 1922 and lasted some 60 years. (It has apparently just resurfaced again in 2013, see here.) It was Camera’s 45th year when Kamoinge appeared in its pages.

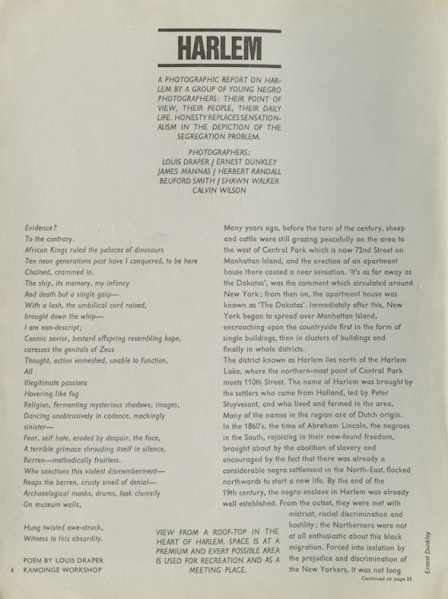

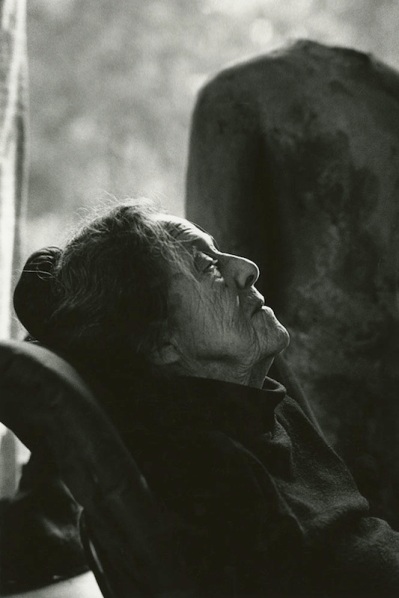

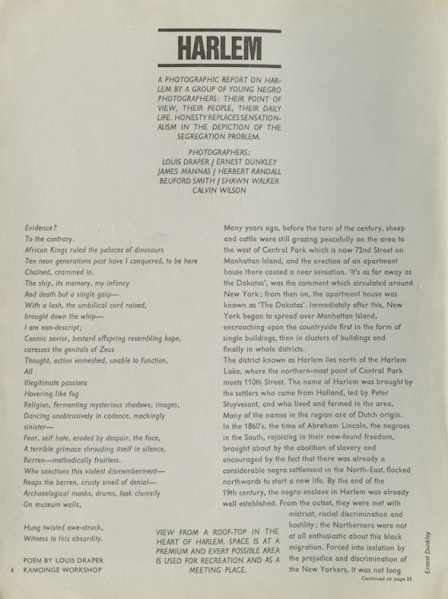

The planning of the Camara feature was done with one editor, but as often happens in journalism, a switch happened mid-stream, and it was the new editor, Allan Porter, that finished managing the piece. Apparently Porter had a very different take on the photography being presented than had been previously discussed with Kamoinge members. The portfolio, with an image by Louis Draper featured on the cover, was controversially (to Kamoinge) titled “Harlem” and subtitled: “A photographic report on Harlem by a group of young negro photographers: their point of view, their people, their daily life.”

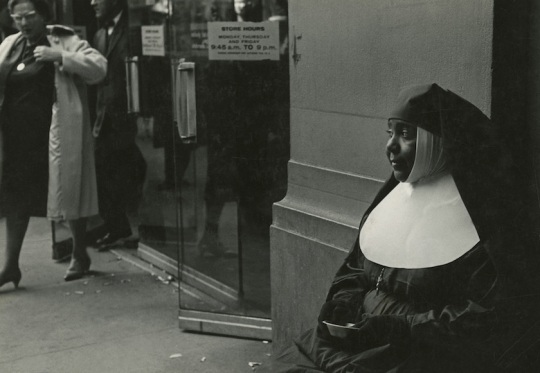

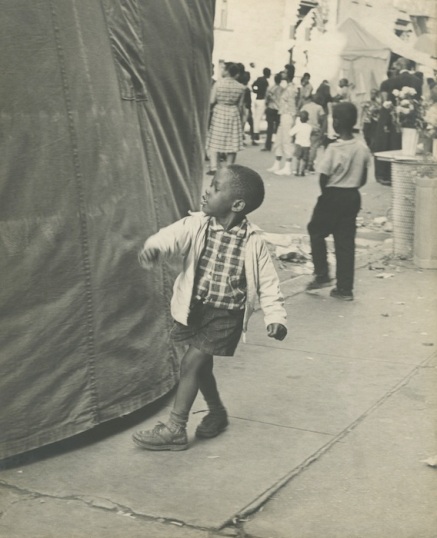

The title and introductory commentary by Porter both framed the Kamoinge photographs, which included work by several members: Draper, Ernest Dunkley, James Mannas, Herbert Randall, Beuford Smith, Shawn Walker and Calvin Wilson, as being an exposé of the “real take” on the Harlem so often portrayed at the time in mainstream media. (Context: this was at the apex of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, with the Harlem riot of 1964 in recent memory, and coincidentally Porter was Camera’s first American editor, giving him a presumably very specific American perception of the positioning of certain race relations perhaps unlikely to be shared by a non-American editor.)

An excerpt from Porter’s introduction which refers to all four portfolios of that Camera issue, including Kamoinge’s:

“All the photographers were personally involved in their subject, and their views are subjective for reasons of personal, racial, national or religious identification. This tends to make the visual portrayal less sensational reportage and more of a personal statement; above all, in each case the camera observes not as a curious outsider peeping through keyholes and pointing a finger, but as an insider, as part of the life it observes.”

pg. 18-19, Camera Magazine, July, 1966, Issue 7, photograph by Louis Draper

However, not all the included Kamoinge photographs were taken in Harlem. Many were taken across the US, and certainly not all, if any, of the photographers were living in Harlem at the time. Kamoinge had shortly operated out of the 139th Street brownstone but that was really the only concrete Harlem point of reference to be made.

Kamoinge members were apparently not pleased with the new positioning of their portfolio and wrote a post script that was published along with the photos:

“The Kamoinge Workshop is composed of black photographers whose involvement with their medium has brought them together to communicate the conditions they see and feel around them. The point of view expressed by these photographers is personal and individual, and their treatment of technical and aesthetic problems when dealing with aspects of the human condition is often radically different to the established approach. They come together to exchange ideas, to forge ahead with their contemporaries and to speak the truth as they see it through their work. The Kamoinge Workshop see Harlem as a state of mind, whether it exists in Watts in California, the south side of Chicago, Alabama, or New York.”

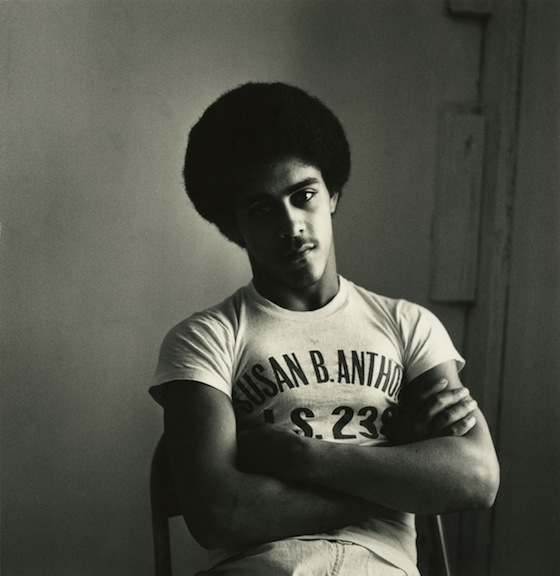

As for Draper’s contributions, along with the cover image entitled John Henry, he had two other images in the portfolio, one of a dapper black man on the street in the garment district of New York City, and another of a woman of color in a leopard-print dress crossing the street in what looks to be the Lower East Side. A powerful poem by Draper was also included to begin the set of images, as seen in the below scan.

In the book New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement (ed. by Lisa Gail Collins and Margo Natalie Crawford), Erina Duganne devotes a chapter section on Kamoinge’s Camera Magazine portfolio entitled “Insiders and Outsiders: The Kamoinge Workshop’s ‘Harlem’ Portfolio.” (pages 190-204) Duganne interviewed Draper to discover that he did not personally know any of his subjects in the Harlem portfolio, and that with the John Henry image in particular (taken in the Lower East Side) he recalled feeling a sense of fear or concern that the man would be angry at being photographed. Duganne says “Draper’s anxiety with respect to his subjects undermines Porter’s assumption that the racial background of the members of Kamoinge necessarily predisposed them to intimately knowing the black subjects of their photographs.” (page 193) And later she puts it poignantly, “Rather than separate their art from their lived experiences, the members of Kamoinge used their photographs to explore the ways in which they informed and complicated one another.” (page 197)

Even with varying perceptions of the Camera Magazine portfolio, the piece gave a certain visibility and professional validation to the Kamoinge Workshop and its members, and was presumably the first case of a group of African-American photographers’ work being highlighted in the magazine for photographers all over the world to see.

Coming soon: Kamoinge, Part 4…the 1970s

In May 1964, Edward Steichen invited Roy DeCarava, who in turn invited the Kamoinge group, to exhibit at Danbury Academy of Art, Connecticut in a fundraising exhibition sponsored by the local NAACP.

In May 1964, Edward Steichen invited Roy DeCarava, who in turn invited the Kamoinge group, to exhibit at Danbury Academy of Art, Connecticut in a fundraising exhibition sponsored by the local NAACP.